The Duke of Hazard: How an Unbreakable Kansas Farmer Bore a Lifetime of Scars

A roadmap of scars on skin was testament to a lifetime in agriculture. On a tightrope between twin peaks of work necessity and danger, all farmers suffer injuries of various stripes, but the unbreakable Ward Henry was a breed apart.

A man of fortitude and incessant good cheer, Ward Henry’s 70-plus years in farming were punctuated by a succession of traumatic machinery accidents including a drill rollover, shooting, anaphylactic shock, amputation, and PTO mangling—as if his flesh attracted hazard. Defeating infinitesimal survival odds, he was undaunted by circumstance, disinterested in excuses, and extremely grateful for family and farm.

Ward’s calamitous tale is the inverse of its initial appearance. Rather, his injury-laden account highlights agriculture’s insatiable need for safety awareness: Danger permanently rides shotgun beside every farmer.

Bumps

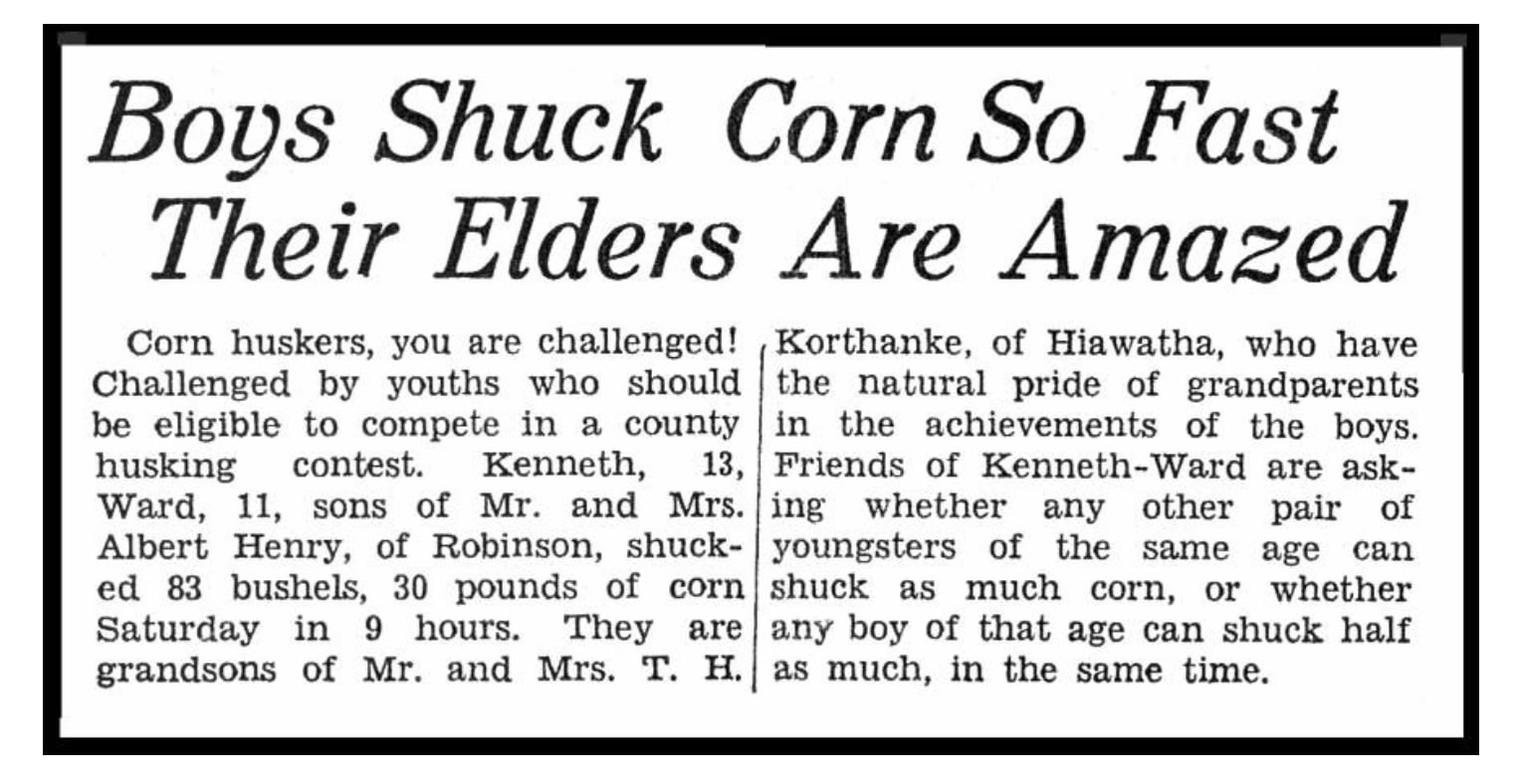

Born in the upper corner of northeast Kansas’ Brown County in 1920, Ward (decd. 2014) witnessed the advent of mechanization in American agriculture and rode the shift from mule to machinery power. His youth in family fields was dominated by the necessity of livestock in the rows, requiring daily harnessing of a dozen horses and mules.

In a 2007 memoir compiled by his grandson, Chris Henry, a professor and irrigation engineer with the University of Arkansas, Ward offered a window into the logistics of mule power: “It was quite an experience going through the fields. I remember we used to walk 10 miles a day, each round was 1 half-mile and we would walk down and back (1-mile round trip). We would make 5 half-mile rounds in the morning and 5 half-mile rounds in the afternoon, because that was about all the mules could stand when it was hot.”

As a small farm boy chasing the shadow of his father, Albert, in the rows, Ward quickly acquired a nickname, Bumps, and the moniker stuck fast with ample justification. At four years old, Ward “Bumps” Henry escaped his first brush with death.

“Literally Unrecognizable”

During the planting season of 1924, as Albert held the reins behind a mule team, young Ward sat atop a drill box, enjoying a knocking ride, blissfully unaware his perch was a potential deathtrap. At the crack of his father’s whip, the mules jumped, the drill lurched, and Ward disappeared. Down between the drill boxes and press wheels, wedged between the row units and pressed into the dirt, Ward was run over by the drill—but emerged entirely unscathed, not a scratch.

The drill miracle was followed a decade-plus later by the staccato pace of further accidents. Gunshot; #9 wire; and bumblebees.

Breaking a winter day’s monotony as a teenager, Ward loaded a .22 rifle, intent on denting the ever-growing population of pigeons nesting in the family barn. Entering the building and drawing on the first bird spotted, his rifle jammed when the brass lodged. Returning to the house, he attempted to remove the cartridge, and carelessly placed his left index finger over the barrel’s mouth. The gun discharged and the bullet blew through Ward’s finger (and perilously close to his head), the shock of blood rendering him unconscious as he collapsed to the floor. Bottom line: the lead projectile missed all bone and nerves, leaving Ward with no permanent harm.

Near the same window in time, Ward came perilously close to losing an eye. After milking cows in the chill of an early morning, he picked up a milker in each hand and walked toward the house, glancing upward to gauge the day’s weather in the breaking dawn sky at the exact moment a splice on a #9 clothesline met him at eyeline. The splice caught his eyelid, almost peeling it entirely off before continuing the cut deep into his eyebrow. Following surgery, the lid was sewn back in place and the brow stitched. Although requiring further surgery, Ward’s eyesight sustained no damage.

A third high school accident, and the most serious of the lot to that point in Ward’s life, almost came with a toe tag. While plowing clover under in spring, he disturbed a ground nest of bumblebees and was attacked on the slow-moving tractor by a raging swarm. Ward’s son, Bob, describes the aftermath. “Dad was severely allergic to any kind of bee or wasp sting. When he hit that bumblebee nest, he got stung countless times above the neck before he could get away. He made it into the house, but by that time his allergic reaction was so extreme that he was literally unrecognizable to my grandmother at first—that’s how massively swollen his head and face were. She used some kind of home remedy on him—I don’t know what—and it acted like an antihistamine and saved him.”

The three teen accidents ended with a relatively mild outcome, despite a sizeable margin for far greater consequence. However, the heavyweight machinery accidents of Ward’s life were yet to arrive and would come close to literally ripping the life out of a Kansas farmer.

Gains—and Losses

Ward’s first significant agriculture equipment experience in the age of mechanization occurred in the 1930s, with the on-farm arrival of a steel-wheeled Fordson pocked with angle iron for traction—a tractor used solely for plowing. (His machinery reminiscences include a surreal, made-for-Hollywood vignette chasing escaped mules across Kansas fields in a no-top Model T Ford.)

By the 1940s and 1950s, mirroring other agricultural operations across the U.S., the Henry farm reached levels of technology and amenities unthinkable only several decades in the past. Ward graduated from Highland Community College in 1940, and began working his own ground, purchasing a Farmall H Tractor, cultivator, lister, and mower for $1,000 total.

He married Virginia Vanbebber in 1941, the same year party-line dial phone service arrived on-farm, with electricity following in 1946. In 1948, Ward observed the first television of his life in a storefront window, and two years later bought a set. By 1956, he enjoyed the chill of his first window air-conditioning unit, a luxury that offset a notably scorching Kansas summer with highs reaching 110 degrees.

Wedged in the middle of the litany of technological gains was an excruciating loss that followed him to the end of his days: In 1948, prior to fall harvest, 28-year-old Ward traded for an Oliver corn picker at an equipment dealership in Falls City, Neb.

Several months later, the two-row picker stole Ward’s right hand.

Doctor’s Choice

Oct. 25, 1948. As stated in Ward’s memoir: “I had gone back to the field to run some stalks through the stalk ejector in the back of the corn picker and I was going back to the front to get on the tractor and there was a stalk feeding in the rolls, so I just reached out to push it down and as I did, it caught, and pulled my hand down into the rolls of the corn picker.”

Fortunate to pull free before the entire arm was consumed, Ward wrapped a jacket around his dominant, right hand, and walked a half-mile across open fields to his farmhouse, walked inside, and collapsed on the floor, unconscious before a shocked Virginia.

Although his fingers were intact, the rollers had inflicted heavy compression damage to nerves and ligaments. Taken to a hospital and sedated to ease the pain, Henry woke hours later to find the hand gone, by doctor’s decision. With antibiotics scarce in post-WW2 northeast Kansas, the attending physician took no chances—amputation.

Ten days later, Ward was back on his farm, and only days after his return—minus a hand—he was harvesting grain again with the same Oliver corn picker. A year later, he was fitted for a prosthetic, essentially a clasping hook. “I had to make some adjustments on the machinery I had,” Ward recalled. “I welded loops on some of the controls so I could work them with my hook and I got along very well. Combines were not as complicated as they are today, there were only about two controls. It was not like it is today, where everything is controlled from one lever and your thumb controls all of the many functions of the machine.”

Despite the pain of a corn picker accident that took Ward’s dominant hand, forced him to become proficient with his left, and affected his physical movement until the end of his days, the loss of a limb paled in comparison to the trauma to come: “The major accident of my life happened in April of 1968.”

Slip of the Hook

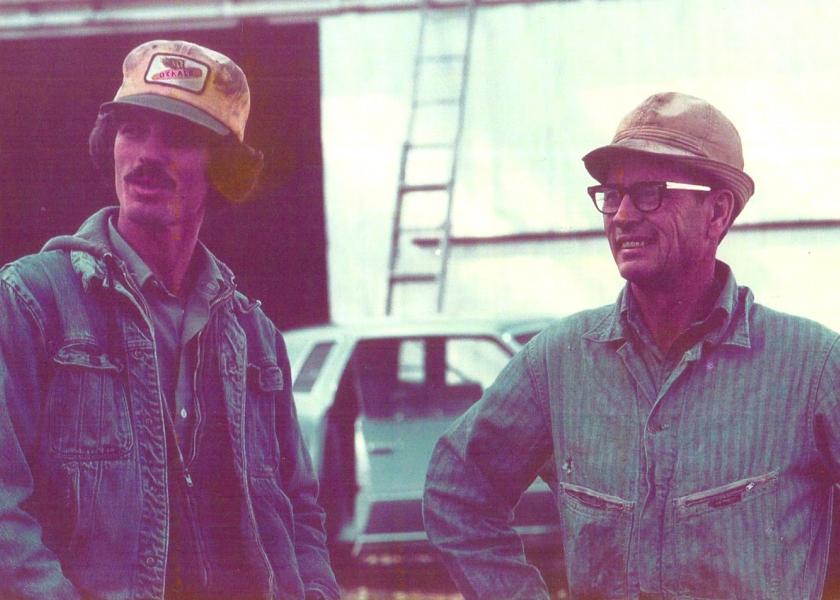

Bob Henry is the firstborn child of Ward and Virginia. At 77, the active farmer has grown corn and soybeans for 55 years, many of those seasons spent at his father’s side.

Born in 1945, Bob has no memory of Ward prior to the corn picker accident and no recollection of his father without a prosthetic hand. “My dad was a man of strength. He lived a ‘shake off the dust and move forward’ attitude and never had an excuse for anything. Certainly, all the physical injuries of his life took a physical toll on him as he aged, but he wouldn’t allow them to take an emotional toll.”

Ward’s lack of a hand was a given—not a handicap, according to Bob. “He had a hook instead of a hand, and that was it. Therefore, there was nothing he couldn’t do on the farm. Nothing. Growing up, I never thought of dad as handicapped because he did everything everyone else did. It really was that simple.”

In the summer of 1967, Bob completed a college degree and returned home to farm. Almost a year later, on an early April day in 1968, roughly two weeks prior to spring planting, Bob and Ward, along with patriarch Albert, took advantage of sunshine and temperatures ranging near 60 F to reset posts on a pasture fence.

The Henry trio utilized a PTO-driven post-hole digger that sat on an A-frame and plugged into the 2-point hitch of an International tractor. The PTO had no cover: “In 1968 there were PTO shields, but we did not have one,” Bob notes. “There was no shield around the shaft.”

Where the PTO coupler hooked to the gearbox, a set screw was supposed to hold a U-joint onto the shaft. The set screw was gone, long replaced by a hex bolt with its head sticking up approximately three-quarters of an inch.

Bob sat in the tractor, running the hitch and PTO, easing the digger into the ground with his hand resting on the PTO lever. Albert stood on the left side of the digger, raking away dirt with a spade as each hole was dug.

The pasture fence ran along a field of relatively hard ground, a condition that sometimes required extra pushing weight to help the digger break ground. Ward was positioned on the right side of the post-hole digger with his hook on the gearbox and his good hand on the A-frame, pulling down to help the auger penetrate the dirt. Ward wore a t-shirt, layered by overalls, and topped with coveralls. It was clockwork progress by three generations of Henrys in unison—until Ward’s hook slipped.

Upon the downward shift of the hook, the cuff of Ward’s coveralls caught in the PTO shaft, and in a nightmarish blink, Ward, 5’10” and 165 lb., was rag-dolled into spinning steel and rocketed across the machinery, the sounds of the violent wrenching swallowed by the din of a tractor engine running at one-third throttle.

Despite his hand on the PTO lever, Bob’s reaction was no match for the speed of the shaft. “I saw the coveralls catch and I reacted as quickly as I thought humanly possible, shutting off the PTO. Too late,” Bob explains.

Hurtled to the ground, Ward landed beside Albert in a broken heap, stripped of every stitch of clothing, save his socks and boots. Bob burst off the tractor and saw his father in extreme pain, but conscious. Along with fractured limbs and extreme overall trauma, his skin was grossly abraded by the high-speed rubbing of denim and canvas as clothing tore away from his torso at tremendous velocity.

“All his clothes were hanging on the PTO shaft and he was covered in so many injuries,” Bob says. “It was a scraping and bruising that is hard to describe. Still, he was alive. In a way, the loss of his clothes saved dad because the shaft stripped him and spit him out—otherwise he would have been torn apart.”

Albert covered Ward with a coat and sweatshirt, and Bob drove the International a mile to the farmhouse, and directed his mother, Virginia, to call an ambulance for Ward. Virginia kept her nerve and asked no questions or sought any details; she instinctively understood the gravity of the situation and responded in seconds with an emergency telephone call.

Bob traded tractor for truck, racing back to Ward in a 1967 International pickup. Placing Ward in the truck bed, Bob sped for the farmhouse, reaching the yard as the ambulance pulled onto the property. Strapped to a gurney, Ward was rushed to a hospital in Hiawatha, precipitously close to losing his remaining hand and arm.

Ward’s body was broken and there was no 10-day recovery repeat of 1948: The Kansas farmer would not return to his Brown County land for four months.

“Losing My Hand Was Nothing”

Along with a broken shoulder, Ward suffered a compound fracture of the humerus and a gruesome twisting of muscle around bone that required surgery and a metal plate. “How I survived, that I'll never know, but it did major damage to my body…I remember not knowing whether I was going to lose my other hand or not. I remember I prayed that I wouldn’t lose my other hand,” recalled Ward.

Day by day, week over week, from April until August, Ward, 48, recovered in hospital and returned home just prior to the 1968 harvest. The physical toll was almost more than he could bear—a fact borne out by his comparison of corn picker versus PTO: “And of the two accidents, if I could have taken away one of them, I would choose the second one. Losing my hand was nothing compared to my incident with the post hole digger.”

Ward farmed another 20 years. “My dad slowed, but he kept going, Bob emphasizes. “He’d permanently lost strength in the left arm and a whole lot of muscle in the accident. Once his arm finally healed, it was just a matter of adjustment. Resilience. That’s who he was. He even took up golf in his 60s, and he never complained or let any of it bother him.”

After Ward’s 1968 accident, safety became paramount on the Henry farm. “It woke me up for life and became a constant reminder to not be careless or get in a hurry,” Bob adds. “Back in the 1960s, we knew we needed PTO shields, but the accidents kept happening, and they still needlessly happen regularly today.”

Chris Henry, UA irrigation engineer, echoes his father’s sentiments: “When we see these unsafe conditions, we all need to think about Ward and correct them so nobody suffers the same fate as my grandfather. Whether it’s an unsafe wiring situation, safety shield, safety glasses, flowing grain, pinch points with implement hookup, or just how we are working around each other, we should all take the time to fix it before we go on. Just remember Ward’s post hole digger.”

“To this day, I can still see what happened when dad got snared by the PTO shaft,” Bob concludes. “I can still the very instant. All it takes is for me to see a PTO, and it takes me back in time.”

To read more stories from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com — 662-592-1106), see:

Cottonmouth Farmer: The Insane Tale of a Buck-Wild Scheme to Corner the Snake Venom Market

Tractorcade: How an Epic Convoy and Legendary Farmer Army Shook Washington, D.C.

Bagging the Tomato King: The Insane Hunt for Agriculture’s Wildest Con Man

How a Texas Farmer Killed Agriculture’s Debt Dragon

While America Slept, China Stole the Farm

Bizarre Mystery of Mummified Coon Dog Solved After 40 Years

The Arrowhead whisperer: Stunning Indian Artifact Collection Found on Farmland

Where's the Beef: Con Artist Turns Texas Cattle Industry Into $100M Playground

Fleecing the Farm: How a Fake Crop Fueled a Bizarre $25 Million Ag Scam

Skeleton In the Walls: Mysterious Arkansas Farmhouse Hides Civil War History

US Farming Loses the King of Combines

Ghost in the House: A Forgotten American Farming Tragedy

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Misfit Tractors a Money Saver for Arkansas Farmer

Government Cameras Hidden on Private Property? Welcome to Open Fields

Farmland Detective Finds Youngest Civil War Soldier’s Grave?

Descent Into Hell: Farmer Escapes Corn Tomb Death

Evil Grain: The Wild Tale of History’s Biggest Crop Insurance Scam

Grizzly Hell: USDA Worker Survives Epic Bear Attack

Farmer Refuses to Roll, Rips Lid Off IRS Behavior

Killing Hogzilla: Hunting a Monster Wild Pig

Shattered Taboo: Death of a Farm and Resurrection of a Farmer

Frozen Dinosaur: Farmer Finds Huge Alligator Snapping Turtle Under Ice

Breaking Bad: Chasing the Wildest Con Artist in Farming History

In the Blood: Hunting Deer Antlers with a Legendary Shed Whisperer

Corn Maverick: Cracking the Mystery of 60-Inch Rows