Bioreactors Take On 'The Dead Zone'

Midwest water quality research on hypoxia management is a work in progress

What do Midwest corn farmers have to do with a crunchy deep-fried flounder sandwich or a bed of oysters? You’d have to reach beyond the tartar sauce to see the connection, but the shrimpers along the Louisiana coast know that activities upstream have been creating a "dead zone" in their fishing grounds that stretches an average of 6,000 square miles perpendicular to the coastline. That’s the size of Connecticut. What’s at stake is a commercial and recreational fisheries business responsible for generating $2.8 billion annually.

The "dead zone" is a huge column of water on and near the ocean bottom that is virtually devoid of life-giving oxygen. Nutrient runoff appears to be the primary culprit, and thus far, water quality research points to nitrate and phosphorus runoff from agricultural activities. This runoff fuels a huge aquatic algal bloom, which decomposes, consuming available oxygen and in the process resulting in hypoxia, or virtual starvation for oxygen, in the living tissues of marine life.

This ecological challenge spurred the formation of the Mississippi River Basin Initiative. Now halfway through a four-year program, the initiative is investing research dollars into targeted watersheds to study ways to reduce nutrient runoff. One of the solutions that is showing some promise is an engineered nutrient trap known as the bioreactor.

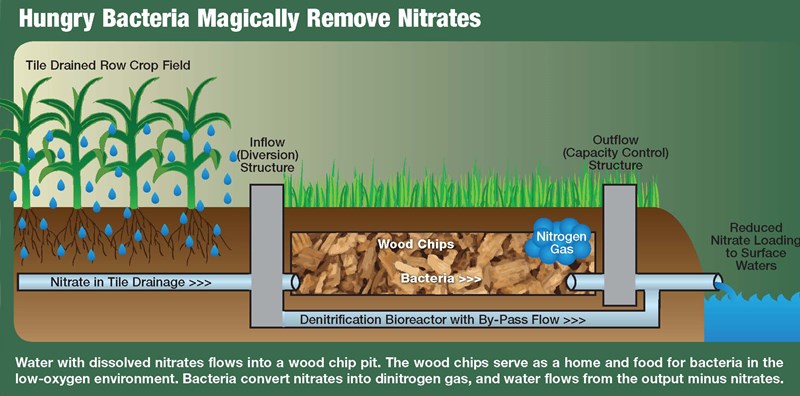

This is basically a pit filled with organic material that contains an input water flow control structure that is hooked up to a field’s tile system. The amount of water drainage from the field is controlled at the input end and dumped into the pit. There is also a water control structure at the other end of the pit that serves as the drainage output.

The biological part of this bioreactor consists of wood chips that provide a carbon food source and home for natural bacteria that break down nitrates into dinitrogen gas. This natural digestive chemical change results in the removal of varying amounts of the nitrate load coming from the drained crop field.

"They’re impressive," says Arlo Van Diest, a corn and soybean farmer based near Webster City, Iowa. "It looks like we’re getting a 70% nitrate reduction, but that might be on the high side."

He has been working with Keegan Kult, a watershed management specialist with the Iowa Soybean Association (ISA), and his local county Natural Resources Conservation Service office. Two bioreactors are installed in different fields. Since these installations can handle drainage only from fields that range in size from 40 to 80 acres, Van Diest says, scaling up to meet the practicality of today’s larger fields might be a challenge.

Richard Cooke, an associate professor of agricultural engineering at the University of Illinois, has been instrumental in designing bioreactors. "One could build a bioreactor large enough to remove the entire nitrate load, but at what cost, and what unintended consequences?" he says. "We recommend designing systems to remove 50% to 80% of the nitrate load based on the tile flow that will not be exceeded 90% of the time."

Kult says that Iowa’s bioreactor pits have been sized at 110'×15', which is a little wider and not as long as Illinois and Minnesota’s pit designs. "The length of the bioreactor mainly determines the residence time, whereas the width has a greater effect on the percentage of peak flow that the bioreactor can handle. Bioreactors are currently being designed to treat 20% of peak flow, with a four-hour retention time within the bioreactor," he says.

"Iowa typically sees 70% of tile discharge from April through June, when not as much water can be stored in the field due to timing, so Iowa’s bioreactors have ended up being wider so they can handle more of the flow at once."

Great benefits. Iowa State University Ph.D. candidate Laura Christianson explains that bioreactors are easy to incorporate into existing fields:

- You can incorporate bioreactors into existing land improvement practices such as grass buffer strips.

- Bioreactors take up a small surface area: less than 0.1% of drainage area.

- This is an "edge of field" treatment, so there are minimal impacts from in-field practices.

- There is a low energy requirement.

- The lifespan is 10 to 20 years (woodchip replacement).

- Cost sharing might be available.

There are some challenges to making a bioreactor effective. Soil scientist Jeff Strock of the University of Minnesota says that bioreactors are incredibly efficient at removing nitrates and phosphorus during the low-flow drainage time of year. "The challenge is during high-flow periods because of a limited flow capacity. Much of that water bypasses the bioreactor system."

While there might be nothing a farmer can do following a "toad-strangler" rainfall other than to open the system, adjusting the stop logs when drainage slows will allow more control of nitrate processing and release. In other words, the bacteria will resume their work feeding on wood chips, consuming nitrates and respiring dinitrogen gas.

"We recommend changing the stop logs a few times a year," says ISA’s Kult. "Once in late July to prevent stagnant flow; then the upper control structure level of stop logs can be raised in the fall when harvest is complete. These levels would be lowered in the spring a few weeks prior to spring field work to ensure that the water table is lowered to a comfortable level. Depending on how fast the water is flowing in the particular tile, one will reinsert the stop logs in the lower structure to get adequate retention time within the bioreactor."

For structural maintenance, aside from wood chip replacement every 10 to 15 years, "stop logs may need to be replaced over time, as the seals can break down," Kult says.

"The biggest challenge is finding time to install a bioreactor. They are mainly located in filter strips, but FSA [Farm Service Agency] restricts access from May 15 to Aug. 1 due to the wildlife nesting season. Once harvest begins, it is very difficult to find a contractor with time to do a bioreactor install, as they all seem to be running seven days a week installing drainage tile," Kult adds. Access to fields might be difficult in spring due to recently planted fields.

"We’ve always been concerned about management on our land," Van Diest says. Bioreactors are a start, but probably not the answer to everything. We have to do something, though, or the government will get involved—and it’s hard to make rules for the whole Corn Belt."