The Golden Age of Storage

Bin building boom strengthens the grain supply chain

Like shiny beacons of prosperity, grain bins and elevators are as indispensable to the grain supply chain as a water tower is to a small town’s water supply. Both secure their valuable contents until needed and guard against scarcity.

In the world of commodity supply and demand, storage has served as an effective risk management buffer, allowing for carryover for year-round buying and selling opportunities.

Having a secure network of on-farm and elevator grain storage is more important than ever with increased global uncertainty from political unrest and foreign currency swings. Not to mention, there are new markets waiting to be tapped. "As a farmer, you can be the best agronomist, producing good yields, but if you have trouble marketing your grain, it’s awfully hard to stay in business today," says Doug Niemeyer, vice president and general manager of Brock Grain Systems, a division of CTB, Inc.

"As a farmer, you can be the best agronomist, producing good yields, but if you have trouble marketing your grain, it’s awfully hard to stay in business today," says Doug Niemeyer, vice president and general manager of Brock Grain Systems, a division of CTB, Inc.

That marketing picture includes the year-round selling and buying opportunities derived from having a scalable grain storage system, another piece of the field-to-port infrastructure puzzle. It is also part of the American agriculture success story—one that includes the production, merchandising and transport of 500 million tons of perishable grain per year, according to USDA.

"We are stubbornly optimistic about the ability of the global food and agriculture industry to meet future grain needs," says Erick Erickson, special assistant for planning and evaluation at the U.S. Grains Council (USGC). Erickson refers to new USGC research that looks at global demand in Asia through 2040.

"Demand will grow phenomenally and the markets will respond. There will be a huge surge in the number of middle-class consumers in the developing world that will want to improve their diets with meat protein," he adds.

Erickson says the U.S. share of exports has seriously eroded in the past two years. "For the first time, the U.S. has fallen below 50% of the world market share for corn."

Tight global stores, two short domestic corn crops and demand for corn-based ethanol production have combined with growing global food demand to drive corn prices to record-high levels in 2011. The high prices have encouraged competitors such as Argentina and Ukraine to expand their sales and have motivated corn importers to look for low-cost alternatives, driving down the U.S. market share.

Both global and domestic demand is creating the storage boom, and "corn is the overwhelming driver of grain storage," Niemeyer adds.

Research group Informa Economics estimates the 2012 U.S. corn crop at 94 million acres, producing a record 14.1 billion bushels. In the Southern states, corn acres continue to increase due to the historic shift from cotton to corn, says Tom Gettings, technical expert at Grain Systems Inc. (GSI). "These are new markets for storage that have never seen chain-loop systems and green field storage setups."

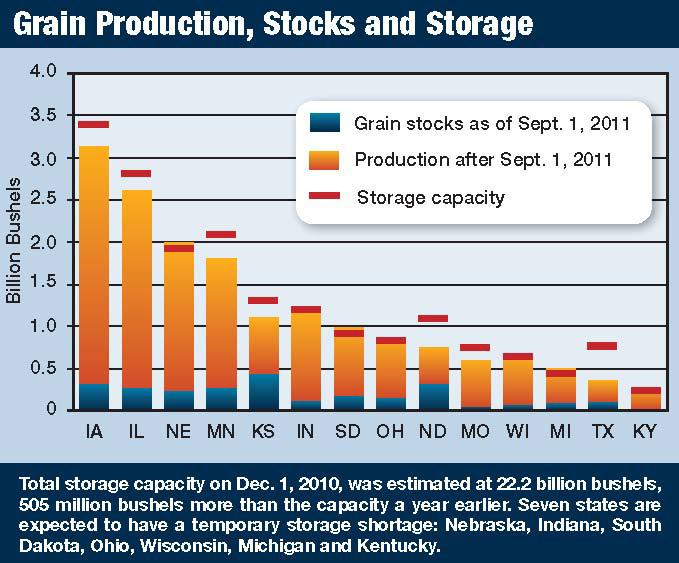

On a national scale, USDA reports that from February 2008 to February 2011, U.S. commercial grain capacity volume increased 15.6%, with nearly half of the increase taking place from 2010 to 2011.

Ethanol and upgrades. Price pressure from government-induced ethanol mandates that went into effect in 2007 created corn demand and storage needs almost immediately.

This year-round market requires corn stocks regardless of whether they are $2 or $10 per bushel, says Wally Tyner, energy policy specialist with Purdue University. "About 27% of the nation’s corn crop must be devoted to ethanol this year to meet the federal mandate," he adds.

There has been some pressure from the ethanol industry to focus on grain quality, which has steered corn producers and country elevators to upgrade to conveyer-type systems, according to John Hanig, sales director with Sukup Manufacturing Company.

"We’re seeing a lot of setups with a minimum of 50,000-bu. bins on farms. That’s better than what the commercial setups were like 20 years ago. During the May through July period, when corn markets peak, it’s easier to sell out of the bins than to forward contract," Hanig says.

Other bin manufacturers agree. "There has been a lot of consolidation in this business with fewer, but larger customers," says Brock’s Niemeyer. "The average bin is getting bigger and everything is designed to load and unload faster. We’re seeing incrementally fewer auger systems installed and more bucket elevator and belt conveyer systems. For on-farm storage, the 48'-diameter bins are popular, as well as the 95'- to 105'-diameter bins. If we get a possible 14-billion-bushel corn harvest this next year, we’ll have a very big demand for grain bins."

Many farmers are adding 600 to 1,500 acres to their current operations and finding they need to upgrade to handle the additional grain, says Gary Sorgius, grain handling consultant for Ripco Ltd. in Otwell, Ind.

"Our business is extremely strong and has grown 15% compounded over the last six to eight years," he says.

His customers look at storage systems as necessary long-term, low-maintenance investments, similar to tiling and irrigation.

The grain supply chain gang. Grain is typically pulled into domestic markets by truck or rail for use in feedlots; hog, chicken and turkey operations; and ethanol plants, or exported in one of three directions: down the inland waterway systems of the Midwest and South by barge to terminal elevators; out to the West Coast to port terminal elevators by shuttle train; or to a few Eastern markets by Great Lakes boats, trucks or rail. The quality and reach of our transportation network, our storage grain banks and the Chicago Board of Trade work together to make American grain competitive in the global markets, but this depends on efficiencies within the system.

|

| The Benson family (from left), Aaron, Danny, Donnie and Don Sr., has provided more than 160 years of service for northeast Missouri farmers. |

Since transportation is a large variable cost, efficiencies within the different modes of transportation have forced a greater economy of scale throughout the grain supply chain by increasing both storage and freight capacities. The faster more grain can be moved along each point in the supply chain, the more profit there is for everybody, from producer to exporter.

GSI’s Gettings says that bins are actually designed to cycle grain with fast turnaround times. According to a recent USDA Grain Transportation Report, a growing number of country elevators are now capable of loading 110- to 120-car shuttle trains within 15 hours.

The economy of scale and grain-holding capacity of elevators and grain carriers, speed of handling and geography are important because the transportation modes operate on a system of penalties and rewards, which shows up to farmers in the basis.

Terminally big. The Bunge elevator in La Grange, Mo., is considered a terminal elevator because it is a step up from the country elevator in terms of capacity. Because it is situated on the Mississippi River, it also can easily load barges, the cheapest form of long-haul transportation.

The advantage can be seen in the basis that inland farmers receive and the distance from the port at New Orleans. A recent USDA–Agricultural Marketing Service report shows a 7¢ per bushel

difference between corn shipped from Illinois and corn shipped from Nebraska to the Gulf.

The elevator buys corn, soybeans and wheat from a 120-mile radius. Bill Klodt, elevator manager, says it offers drying and blending services for its customers and 99% of its grain is shipped to the New Orleans port by a barge fleet service from Quincy, Ill.

The biggest challenge is handling throughput, particularly during the harvest season, he says. Keeping elevator machinery running and coordinating enough barges to move product downstream so more grain can be received is challenging. An efficient river elevator facility can load a 60,000-bu.-capacity barge with a 9' draft in a couple of hours.

Four generations of service. The Hassard Elevator Company is an impressive sight, sitting among crop fields just off of Highway 36 near Monroe City in northeast Missouri. It could serve as a museum of grain storage, with four distinct groupings of storage bins, the earliest represented by a 1918 wooden elevator. The elevator is owned and operated by four generations of the Benson family. Recently "retired" from the business, Don Sr. and his grandson Aaron talk about the changes and challenges of running a country elevator, which moved more than 2.5 million bushels of corn, soybeans and wheat for local farmers in 2010.

Having worked in the business for more than 65 years, Don remembers when farmers hauled their grain in wagons and the Wabash Railroad operated a spur from the elevator to haul grain to St. Louis markets or to the river for barge transport. "Railcars became hard to get a hold of, so we started shipping by truck."

Don says that in 1966, the family primarily handled soybeans. Then they bought a grain dryer and started handling corn. "I’d make a bid right at the [farmer’s] bin and then take it directly to the Quincy soybean plant, which is about 40 miles from here or the river terminals," he says.

"We still do that today," Aaron says. "We sell to Bunge at the river and ADM in Quincy and two ethanol plants for corn and the St. Louis market for wheat, corn and beans. The basis has improved since the ethanol plants have come into the area.

"The big challenge in the grain business is obtaining operating credit to meet the margin calls," Aaron adds. "Right now, we’re already buying grain for 2012 delivery and we hedge it. The price could go either way; if it would happen to go up, then we’d have to give our brokers margin money every day it goes up. We don’t know where the high end will be, which means we don’t need an unlimited amount of credit, but we do need enough to meet the margin calls."

In the future, Aaron says, their growth will likely come with direct business. "Farm operations are getting larger; they’re buying their own semis. They’ll sell the grain to us, but deliver it to another elevator where they’ll get the higher price, and it will all be run through our elevator," he adds.

The Hassard Elevator Company reflects the current golden age of storage. It also celebrates the optimism of our American agricultural enterprises that are planning and building for the future to meet the world’s challenging grain demands—from field to port. \

Read more about our nation's infrastructure challenges.